Video Review Below:

Clash of the 501’s

I recently posted a blog about the Peugeot PH501, though it doesn’t feel recent. It was actually in January, before the pandemic began and when normal, mask-free life was taken for granted. It seems another world, even though I’m posting this just 6 months later. These are strange days indeed, and especially now that I’m visiting America, right in the eye of the storm. The love of bikes doesn’t stop, however, and I’ve been lucky enough to restore this vintage Trek bike, a 500; it’s interesting to compare it to the Peugeot.

The opportunists

The story of Trek is impressively bold and audacious: in 1976, two Americans decided to take on the big European bike brands and win the share of the mid-range US bike market. Failure had a big part to play in the birth of the Trek brand; Dick Burke and Bevil Hogg owned 2 bike shops the previous year, but they folded and their vision of owning a nationwide chain of shops quickly ended. But great ideas can be born in the ashes of failure; instead of giving up, they decided to build their own bikes, creating hand made frames to take on the Europeans.

European Quality

I’ve owned quite a few Treks, a 410, a 500 Tri Series, a 520, a 620 and 300 Elance. I’ve been impressed with all the Treks I’ve owned, and I think I can say that the quality of all these bikes matched the Peugeots and Motobecanes I’ve also possessed. This 500 was a mid-range bike worth around $400 in 1983/84, around the same price as a Peugeot Ventoux or PH501. Trek bikes of this era are always more understated than their European counterparts, they were never flashy or ornate, but they were nevertheless handsome bikes.

What to Look For

I really like the head badge. It’s an icon of classic Trek bikes, handmade steel frames built in Wisconsin between 1976 – 1983. But you don’t find Trek bikes with half-chromed forks or stays; are there any? Neither do you find stamped fork crowns or ornate lugs on these mid-range bikes. Trek built a culture at this stage that seemed to focus on simplicity and modesty, perhaps as a deliberate contrast to the flair and élan of French bikes.

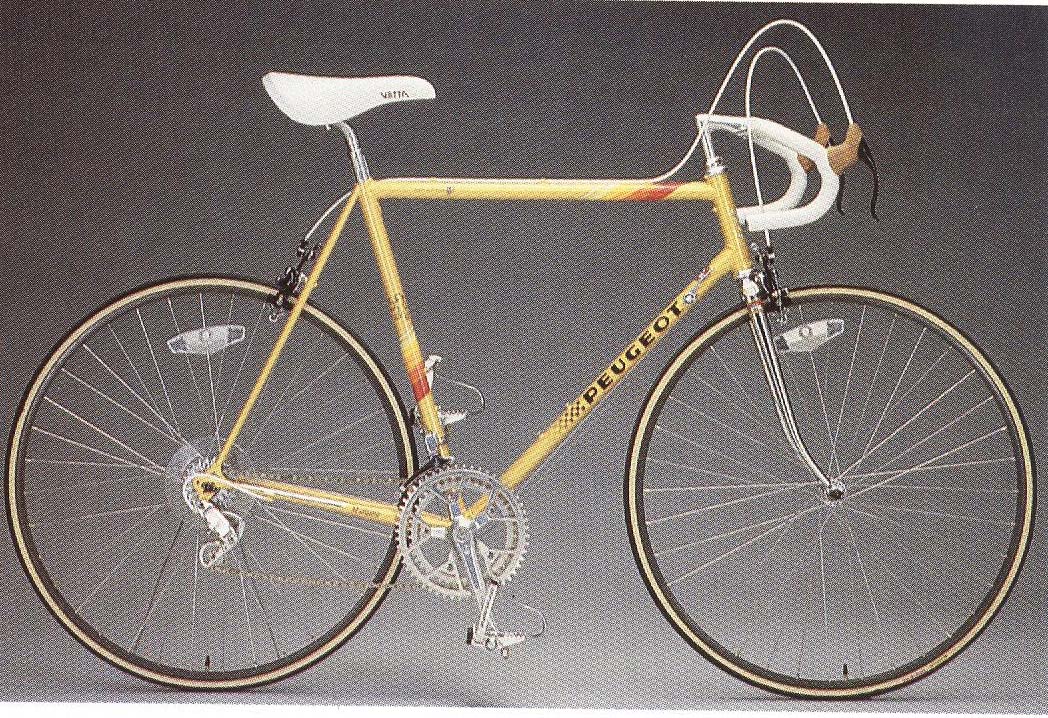

A Mid 1980’s Peugeot Mont Cenis

American Engineering..

American engineering, specifically in transportation, always seem to be driven by the attitude that bigger is better. Every time I arrive on American shores, I’m struck by the size of the cars, the trucks, the motor bikes, the RVs. Classic American cars always seem to be huge, gas-guzzling monsters. Wasn’t it Enzo Ferrari who said “Jeep is America’s only real sports car”? But when it comes to a road bike, all that aggrandising goes out the window; a road bike has to be light, sleek, made with the least raw materials possible and ultra-efficient. America had no real tradition in making these machines, no distinction or identity within this field; the modesty of Trek bikes of this era seem to express a certain humility, a deliberate and respectful acquiescence, to this fact.

Brand or Bland

Prestige and patriotism count for a lot in the cycling world. I remember how I dreamed of owning the Peugeot that Robert Millar rode in the mid 1980’s when I was at school. I also wanted a TI Raleigh Team bike, because it was British and it had won the Tour de France. You can deny it all you like, but these are heavy influences on the brand of bicycle you will choose, especially if it’s a road bike. So, with this in mind, a Peugeot would have been my choice without hesitation. I’d never even heard of Trek in Britain in the decade of Millar, Sean Kelly and Bernard Hinault.

Japanese Parts

Japanese engineering has developed a great reputation over the decades. I remember, back in the 1980’s, that when something was “made in Japan”, it generally produced the reaction that it was more reliable than a British product. I don’t think this bike technology shows anything but the same story; the Japanese brand Suntour had succeeded in building their versions of Simplex, Huret and other European components, but at a cheaper cost. Trek chose to put the cost-effective first, this was their brand philosophy in this mid-range market. But I’d choose French parts, like Simplex and Stronglight, over these SR and Suntour components on this bike.

So Which One?

Personally I would go with the Peugeot. Yes, this one above hard a bent fork, but one in the same condition as the Trek would be my choice. Perhaps the Trek is the slightly better bike for the quality of the frameset and paintwork, but there’s no doubting that the Peugeot was a fine machine in it’s day. I just think it comes down to two things: aesthetics and tradition, which must make Peugeot the winner. Oh, and I nearly forgot: I prefer the French components, too.

The 70s and early 80s Suntour components outperformed and weighed less than their Europen counterparts, by miles. The only thing “Cheap” about a pre-1984 Suntour derailleur was the stigmatizing price point. The Suntour ARX is one of the smoothest shifting, durable, problem-free, mid-range, mass bike derailleurs of the early-mid 80s. There’s no comparison to performance with an equivalent Simplex SX610 or early 80s Huret Rivals. I’m saying this as someone who is also a purist and has maintained Simplex derailleurs on Peugeots in working order for years. I can disassemble, rebuild, grease, and tension one in fifteen minutes; but Simplexes have never functioned completely right without user servicing, and the mechanical knowledge of disassembly, cleaning, greasing, and tensioning of both spring bolts, even when they came new on the bike. There were serious racers in the 70s and 80s who ditched their Campagnolo rear mechs and threw a Suntour into their Campy group set, because Suntour Vs, ARXs, Superbe Pros, and even their low midrange offerings outperformed and outlasted highly overrated for the cost, pre 90s Campy derailleurs. Suntour was one of the best performance secrets in bike components for people in the know, willing to get past a Europhile bias. It’s time to admit, as beautiful as old school Euro mech is to look at on classic steel, steed, by the early 80s, Suntour and Shimano were killing them with better performing derailleurs for the price value.

I agree with you on some points, Suntour and other Japanese parts overtook most European rivals in the early 1980’s, as far as functionality is concerned. I disagree with you, however, about the Simplex criticism; I’ve always been a fan of the SJ and SX series, my experiences have always been positive with this series, much less with the plastic delrin versions. Most of all, though, is the aesthetic difference: the Simplex SX and SJ are just far more attractive than their Japanese rivals of the day. This is very important in the realms of this vintage bike culture otherwise, lets face it, we’d all be riding highly functional modern bikes with their bland but efficient mechs.